|

|

|

|

|

| PAUL

GLOVER ESSAYS: community

control of food, fuel, housing, health care,

planning, education, finance. |

| HOME | INTRO | CURRENCY | SUCCESSES | HOW-TO BOOK | PUBLICITY | ESSAYS |

|

|

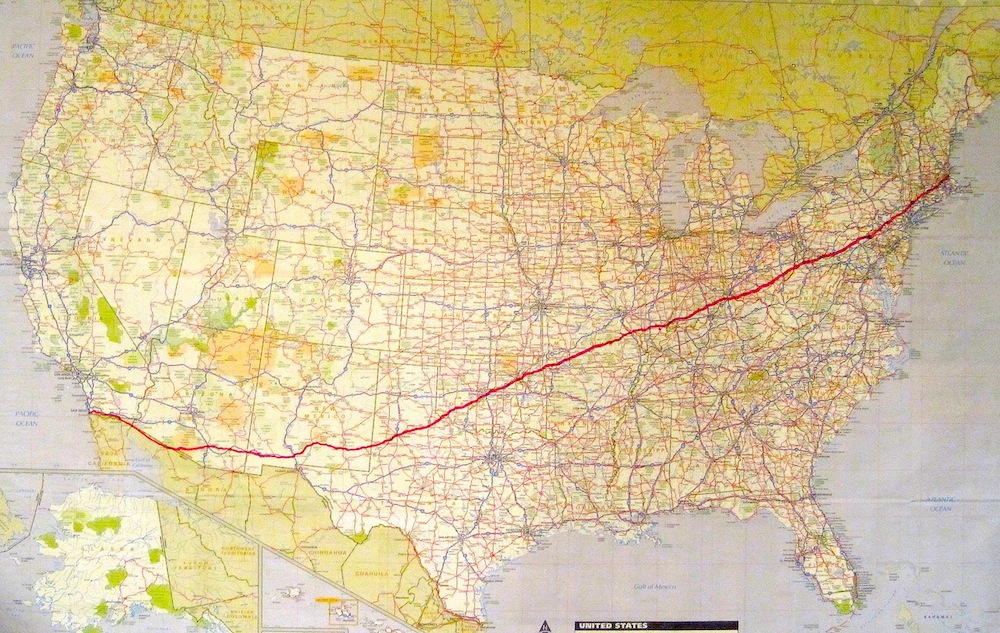

June

8- December 24

Walking the entire distance from Boston along a maze of quiet dirt and gravel roads, swimming and wading rivers, crossing fields, pastures, deserts, forests and mountains, by day and at night, in rain, hail and blasting sunshine, I've arrived in Arizona. Three thousand miles so far, a distance greater than the diameter of the moon, or halfway to the center of the earth. The people I've met and befriended have been the rural folks who live at the far ends of untravelled roads, who occupy beautiful unvisited places. Most of them are miners, housewives, dairy farmers, preachers, hog farmers, cattle ranchers, Amish, cops, Native Americans, migrant workers, orchardists, beekeepers, factory workers, other hikers, reporters and the kids who escort me along paths. Among the rest are crowds of city folks fleeing city crowds: teachers, industrialists, artists, musicians, architects, a multimillionaire and an inventor. They've been generous. I've come from the woods to their backdoors, worked and played with them, shared meals, attended parties, reunions, ice cream socials, and learned more of enduring worth from them than schools offer. I've worked along the way to buy supplies. Since Missouri I've picked apples in a migrant camp, taught half a day of school, hauled lumber, designed a t-shirt, mopped floors, joined a carnival, drawn portraits, and built a donkey shed. Although I nearly froze one cold stormy night when high winds tore my tent away over a cotton field, weather has been generally dry and warm as I walked southwestward across MA, CT NY, NJ, PA, WV, OH, IN, KY, Il, MO, AR, OK, TX, NM, to AZ. Animals of our remaining wilderness fear humans. I've encountered weasel, coyote, wolf, antelope, deer, woodchuck, raccoon, hawk, eagle, quail, vulture, horned toad, viper, rattlesnake, and many more. The only bothersome critters have been mosquitos and dogs. The whole world is a bed. A tired hiker finds comfort in apple orchards, barns, pastures, sheds, forests, log cabins, teepees, wagons, abandoned homes, haystacks, churches and churchyards, greenhouses, trailers, picnic tables, porches, gazebos, schoolyards, public parks, stables, grandstands, sand dunes and backyards. Many people have taken me into their homes. DESERT WALK

Ready to walk across the desert? Pack your overcoat and

suntan oil. Bring fifty pounds of munchies, grab a jug of

water and let's go. All set? Our trail winds one

thousand miles west from Ropesville, Texas over cactus barrens, short

grass and sand dunes.Some of you are hesitating. Why walk across the desert? You have visited this furnace when you drove to the Grand Canyon. Or you flew over it on a business trip, glad to be high above and far beyond. It was large enough. Does it improve a person to walk across the desert? Is there gold-in-them-hills, or are West Texas, New Mexico and Arizona unfortunate obstacles for a continental hiker? Farmers and ranchers love the desert for its own sake. The Texas caprock is perfectly flat and treeless. The only thing in view is distance. A cotton planter refuses to forest the cap to hold soil and moisture: "With all those trees around you couldn't see anything." Six generations of Anglos have worked this prairie and the work has bound them to the land. Their skin is sandblasted and their blood is red earth. But I am a hill country easterner, blood spangled with autumn leaves, and my work these days is walking. What is the desert to me? Last week I followed a line of barbed wire between Chinese Canyon and dry Hackberry Creek, toward Roaring Springs. Scalded sandstone and clay border a gullied plain littered with calcareous pebbles and occupied by yucca, prickly pear, spanish bayonet, grease grass, goat spurs, thorns, and rotting bush roots. Scampering underfoot are red ants, tarantulas, tumble-bugs and gnats. By noon the heat had piled high and thick on the ground. The world wilted. Even barbed wire hung limp. I sought shade. After a half mile metal reflected from far ahead. The reflection became many reflections, the blades of a windmill. Beside it, too good but true, were two large round tubs, moss-bottomed, nearly full of cool water, and shaded by hackberry trees. Whenever the breeze stiffened the blades turned, turning gears which raised and lowered a piston which sucked water to the surface, and spilled water into the tub. I lounged in this pond surrounded by platoons of frogs, tadpoles, water bugs, beetles and striders which must have been imported for the occasion, and stared out from the comfort of an oasis at a fiery universe. The first lesson of the desert is learned. It is burning into me a respect for water and a reverence for its fruits. |

AMERICA THE HARD WAY

Grapevine,

January 23, 1979

Those who tire of routine should start walking across the United States. Start tomorrow, start tonight, take twenty dollars and walk southwest from Boston for six months. Then walk northwest for two weeks. Where will it get you? To new places constantly, exposed to people, animals and storms. To novel encounters daily. Through forests which terrify and delight. Across fields, deserts, mountains, and rivers. To the Pacific Ocean at San Diego, California. From June 8 to Christmas Eve I crossed this continent entirely on foot, taking 199 days to learn about our people and land. Everyone knows this is an enormous nation. Formidable to drive across. Measuring it with my body, I found it more enormous than any book, photograph, statistic, or voyage by car, train, plane or bicycle can suggest. It sprawls nearly limitless between oceans. Walking twenty to thirty miles daily westward across a globe turning nearly a thousand times faster in the opposite direction, resting to enjoy scenery and people, visiting industries and farms, this continental hiker found dramatic changes in American Ways. The whole nation is migrating and mingling as never before. Crowds escaping crowds are flocking to rural areas and shoving agriculture from the land. Suburbs especially are mere architectural smogs caused by large populations shifting with the availabilty of jobs. In them local loyalties fade. What remains of a New York character, a Massachusetts, Ohio, Indiana, Oklahoma, or Texas type? I have walked across seventeen states through backwoods and barnyards. If there are typical hillbillies or Hoosiers, I met them. It was once easy to cross this country and find regional types of Europeans as distinct in dress, dialect and customs as Indian tribes. In 1831 de Toqueville found Americans as varied as the lands they farmed: "Americans of the West were born in the woods and they mix the ideas and customs of savage life with the civilization of their fathers. Their passions are more intense..." Even until the Second World War, Americans tended to identify themselves with geographical place, with the land, and to particular qualities of rainfall and sunset, understanding the meanings of these things to raising food. Since World War Two a national interstate highway system has cut through the mountains which kept subcultures remote. And television began to broadcast our national identity, funded by an intensive automotive and industrial "service" economy, with most people expecting that someone else would somehow put food in the store. Lubbock, Texas, for example, has boosted itself into the Twentieth Century as a proud manufacturing metropolis. But the botom has droppped out of the Panhandle's water table: they sucked it dry, and crops fail worse yearly. Unless they can pipe water from the Mississippi River as planned, a million head of Texans will stampede to your town. Las Cruces, New Mexico is also typical. I had come from mountains of boundless calm to find 50,000 people respectably busy destroying a fertile valley with screwball growth. They are good people, but they are a great mass growing beyond local agriculture, trying to feed the market economy rather than themselves. The area's Comprehensive Plan says plainly, These plans were neither based on citizen-derived Goals and Objectives nor on ecological considerations." (p.51, SRGAPC Report 5). Even Ithaca, New York, a lovely upstate village-city full of lively people and built on fertile soil, considers hooking itself to the industrial highway network, to transform itself into a major Buffalo-to-Binghamton truckstop. In the midst of this upheaval of lifestyle and land use there remain some traces of regional culture. These appear at local festivals, church socials, and family reunions. There is still the Bible Belt and the cowboy hat. Frog fries are relished in Missouri, and Ohioans will direct you "right swack up yond' holler." Kentucky boys spit because spitting is "regular." Pennsylvanians go howling after coons. Hillbillies have moved into trailers. They sweep and mop at hillbilly tourist traps. And there is still the old Ozarker who worked a long day and "let bust with" a few ringing syllables of a mountain song that has reconciled misery and love for two hundred years. Ethnic regions of Germans, Czecks, and Swiss persist. There are areas dominated by red people; there is a village populated entirely by blacks; and strong memories of a town once exclusively female. Generalizations about local character are occasionally true and usually not. They apply as well elsewhere, where they also do not apply. Americans are simply overwhelmingly American. They are everywhere very decent, magnificent and ignorant. They are generous and loveable; they hog the earth and blight the land. In every hill and holler, highland, forest, meadow and plain they will continue to mingle and to learn, by intelligent transition or headlong catastrophe, to bind their lives to the resources of the land. |

| HOME | INTRO | CURRENCY | SUCCESSES | HOW-TO BOOK | PUBLICITY | ESSAYS |

|